Coordination has to do with the bonds between transition elements. These elements are special because they have electrons in \(d\) -orbitals (unlike main group elements, which only have electrons in \(s\) - and \(p\) -orbitals). It’s pretty easy to predict the color and magnetism of coordination compounds because they follow set patterns.

The Coordination Sphere #

Coordination compounds are made up of a complex ion and one or more counter ions. The complex ion, also known as the primary coordination sphere, consists of the central metal atom or ion along with attached atoms/ions known as ligands. The metal ion is an electron acceptor and receives electrons donated from the ligands. Ligands are attached to the metal with at least one lone pair of electrons.

Let’s break down the following coordination sphere:

$$\ce{[Fe(NH3)6]^{3+}}$$

Here, the central metal is \(\ce{Fe}\) . The ligand is \(\ce{NH3}\) , and there are six of them attached to the metal. The overall charge of the complex ion is 3+.

Counter ions aren’t always written out in the equations of coordination spheres, but you need them to keep the charge neutral, so just assume they’re present.

We can count out the charge of the complex ion by adding up the charges of its components. Going back to \(\ce{[Fe(NH3)6]^{3+}}\) , \(\ce{NH3}\) has a charge of 0, while the overall charge is 3+, so the \(\ce{Fe}\) ion must have a charge of 3+.

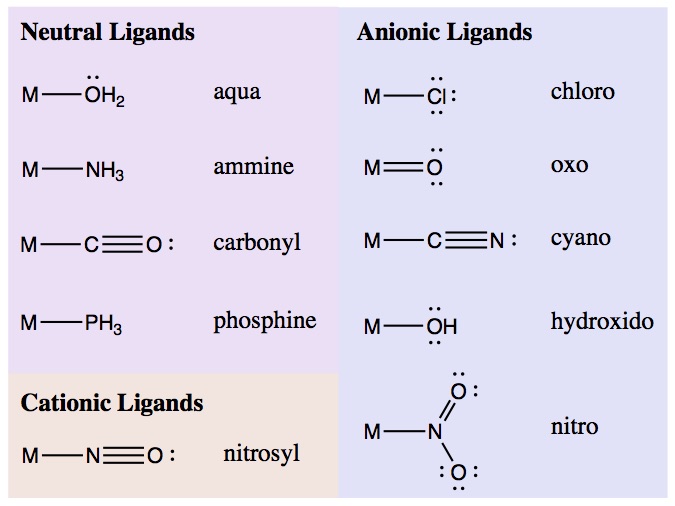

The following table shows the charges of common ligands:

Common ligands with charges. M represents a metal.

An important note here: the charge of the ligand is the charge when both of the atoms in the ligand-metal bond are associated with the ligand. In other instances, charge is calculated by splitting the bond electrons evenly between the two atoms, but that is not the case here.

Common Geometries #

Similar to covalent compounds (as seen using VSEPR theory), coordination compounds also have a variety of structures based on the number of bonding and non-bonding electron pairs around the central atom.

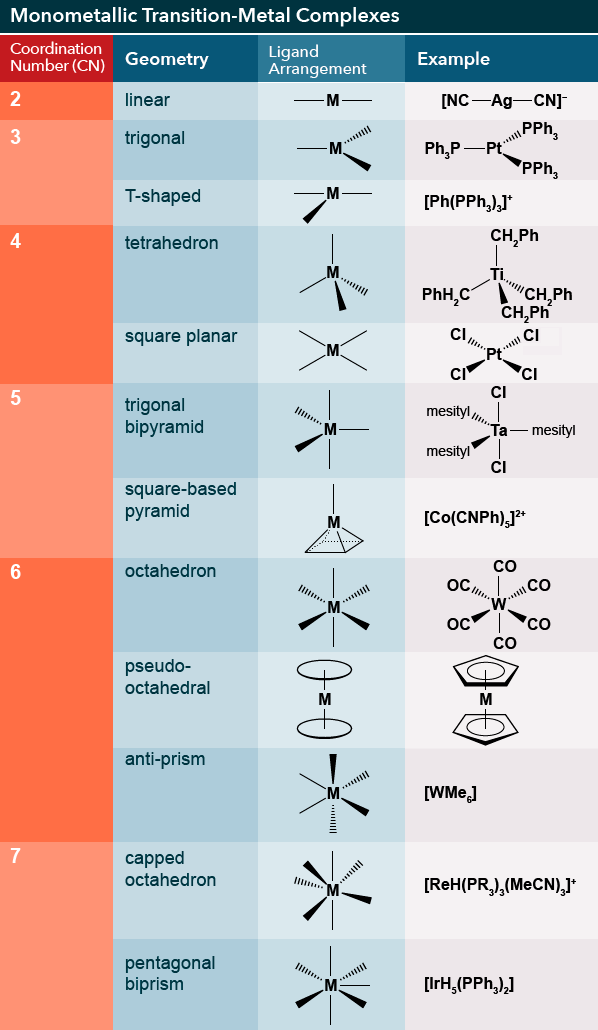

The following table provides an overview of these geometries:

Coordination compound geometries.

The term coordination number is often used rather than VSEPR’s “steric number” or “electron domains”.

Crystal Field Theory #

We’ve seen that atomic orbitals play an important role in chemical bonding. This is also true for coordination compounds, which are unique in their use of \(d\) -orbitals. Crystal field theory is an electrostatic theory (meaning it focuses on the charges and energy) that is centered around the idea that the energetic effects of the ligands are dependent on the geometry of the compound.

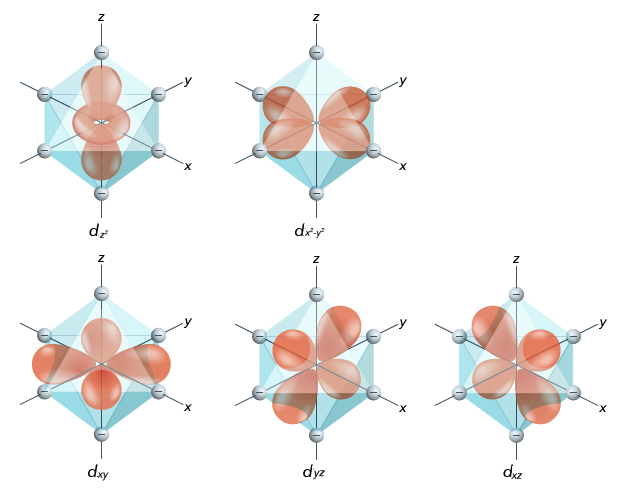

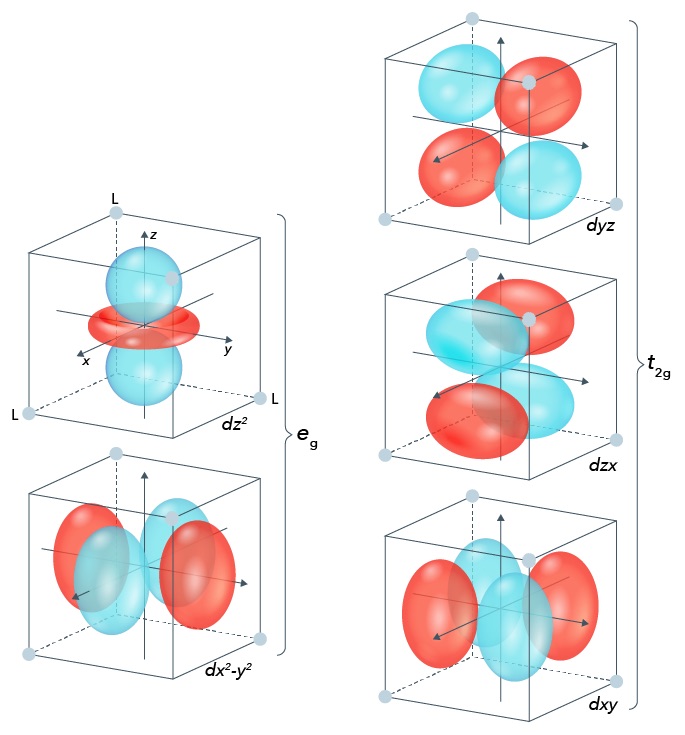

Here’s an example with an octahedral geometry:

Ligand positions in a coordination compound with octahedral geometry.

Here, all the ligands are located on the axes. What’s interesting is that three of the different \(d\) -orbitals – the \(d_{xy}\) , \(d_{yz}\) , and \(d_{xz}\) orbitals – have the orbitals located between two axes, while the two others – \(d_{z^2}\) and \(d_{x^2-y^2}\) have the orbitals along axes. Since the latter two orbitals (also known as the \(\bm{e_g}\) set) are closer to ligands than the other three (the \(\bm{t_{2g}}\) set), they will experience greater repulsion between their electrons and the ligands’ electrons, which makes them higher in energy. In an octahedral geometry, the energy difference between the \(e_g\) set and the \(t_{2g}\) set is noted as \(\bm{\Delta_o}\) .

In a perfectly spherical geometry, it’s expected that all the orbitals have an equal amount of energy. This value is known as the barycenter. It’s been calculated that the barycenter is about \(0.4\Delta_o\) greater than the \(t_{2g}\) set and \(0.6\Delta_o\) less than the energy of the \(e_g\) set.

The crystal field stabilization energy is the energy difference between a spherical field and an octahedral field. It’s simple to calculate:

$$\text{CFSE} = (-0.4\Delta_o)(\text{number of } t_{2g} \text{ electrons}) + (0.6\Delta_o)(\text{number of } e_{g} \text{ electrons})$$

When comparing two compounds, the compound with the lower CFSE will be more stable.

In a tetrahedral configuration, the ligands’ positions look more like this:

Ligand positions in a coordination compound with tetrahedral geometry.

Now, the \(t_{2g}\) set is higher energy than the \(e_g\) set. The energy difference here is labeled \(\Delta_t\) , and the barycenter is \(0.6\Delta_t\) greater than the energy of the \(e_g\) set and \(0.4\Delta_t\) less than the energy of the \(t_{2g}\) set.

Since there are more ligand regions surrounding the metal ion in an octahedral configuration, there is more repulsion going on, causing \(\Delta_o > \Delta_t\) .

Finally, let’s look at the square planar geometry, which is basically like the octahedral geometry but without ligands on the \(z\) -axis. In that scenario:

- \(d_{yz}\) and \(d_{xz}\) : low energy since they’re not close to the ligands

- \(d_{z^2}\) : not as low energy but still pretty low because only the ring orbital is anywhere near a ligand

- \(d_{xy}\) : OK, at least it’s on the same plane as the ligands

- \(d_{x^2-y^2}\) : it’s on the \(x\) - and \(y\) -axes! Just like the ligands!

These geometries affect how electrons are filled. Let’s say we have an octahedral configuration, which means three low-energy orbitals and two high-energy orbitals. We fill each of the low-energy orbitals with one electron. Now, do we:

- Put an electron in an empty high-energy orbital?

- Completely fill all the low-energy orbitals before moving on to the high-energy ones?

These scenarios are called a high-spin and low-spin configuration, respectively. (Confused about the name? Consider that a half-filled orbital has a spin of \(\frac{1}{2}\) , while a fully-filled orbital has a spin of zero. Add all the orbital spins up and see what you get.)

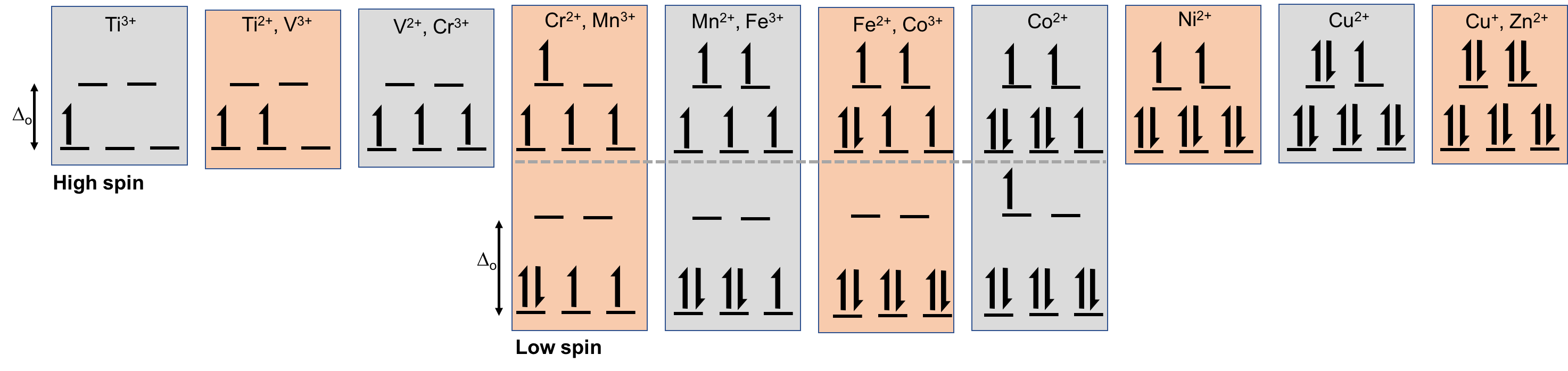

Here’s a helpful visualization:

High vs. low spin with different numbers of electrons.

A high \(\Delta_o\) causes a low-spin configuration, while a low \(\Delta_o\) causes a high-spin configuration.

It’s worth noting that crystal field theory is an electrostatic model. It’s not very comprehensive; for example, it doesn’t address covalent bonding. A related theory, ligand field theory, attempts to combine crystal field theory with molecular orbital theory to cover for this shortcoming.

Factors Affecting the Crystal Field Splitting #

The main factors that affect crystal field splitting energy ( \(\Delta\) ) are:

- Identity of the transition metal

- Oxidation of the transition metal

- Identity of the ligand

- Geometric ligand field surrounding the metal (don’t worry about this one)

Experiments have shown that \(3d\) atoms tend to have high-spin configurations, while \(4d\) and \(5d\) atoms have low-spin configurations. This is because \(3d\) atoms are physically smaller, resulting in less space for electrons to occupy. This increases the energy required to make an electron pair. As a result, it’s easier to just half-fill everything first and then go back for seconds. \(4d\) and \(5d\) metals have more space, so this is less of a problem.

Higher oxidation states create a higher CFSE. This is pretty straightforward – a higher positive charge will cause electrons from the ligands to be more attracted to the metal.